We all try to do good things and ensure that every child gets the quality education they deserve but we often question ourselves “Are we doing enough?” Organisations think about scaling up almost instinctively. The ones that succeed use some strategic thinking about what scale is meaningful for them, and how they should go about achieving scale. In the social sector, thinking about scale is often insufficient, considering the wide array of factors that influence the process.

To learn more about this, we invited our Global Advisor Mr Sakil Malik to have an interactive session with the LLF team and discuss some important questions like-What scaling up means, especially in the public education ecosystem where it is commonly understood as working with governments and addressing myths and misconceptions about the measurement of impact and sustainability in the public education sector.What does scaling mean and what are some factors that impact the scaling-up process, especially in the public education system?

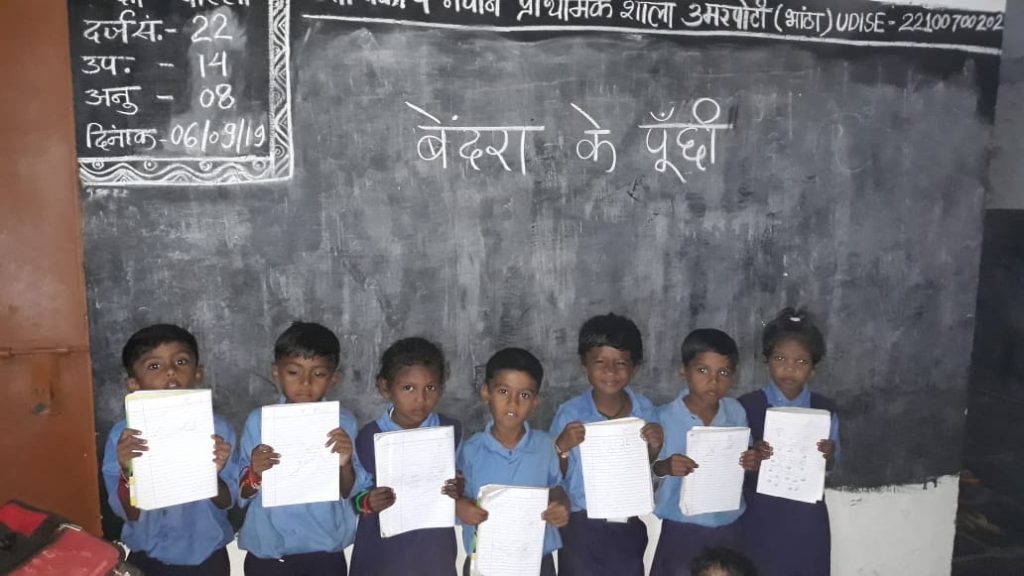

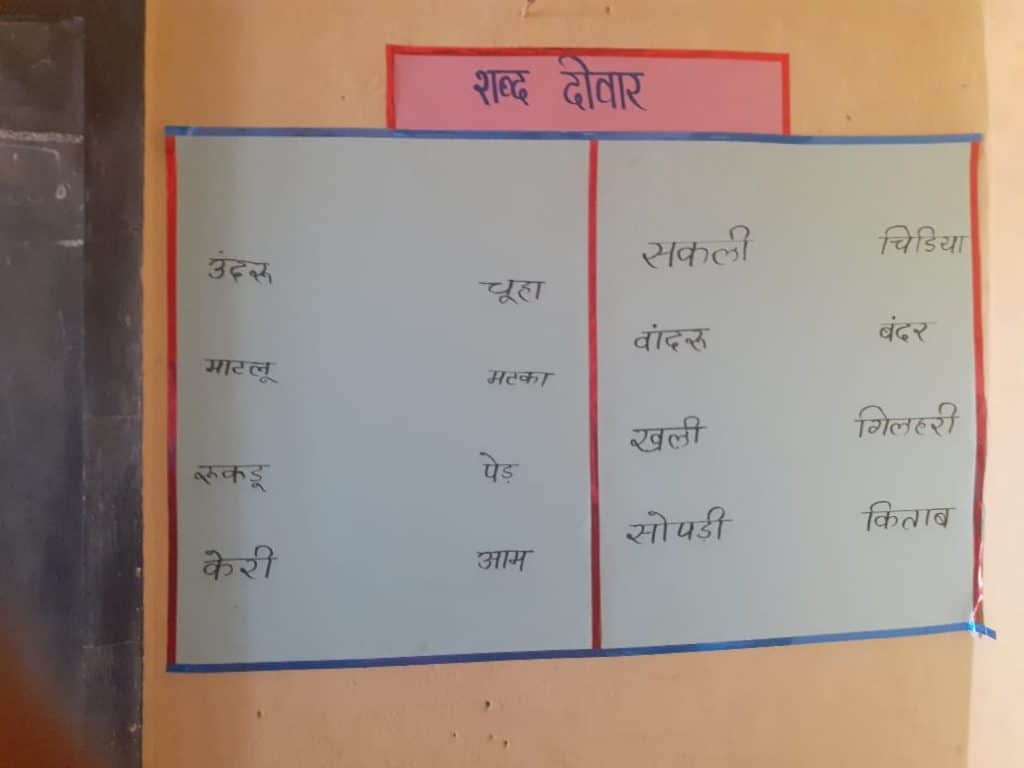

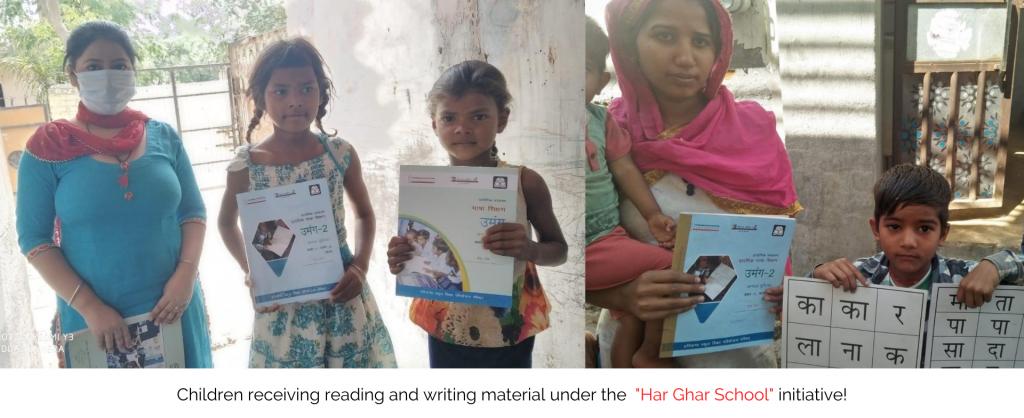

Scale-up actually is a very simple term, which basically means you start doing something small and you want to expand it to the entire community. So very simply speaking, I want to start working in one school, two schools, five schools, ten schools, then I want to expand it to the entire state, I want to then take it to the entire country. But amazingly enough, the last twenty-thirty years of history doesn’t show us any efficient instances of scaling up. Now, going from 100 schools to 900 schools, will you call it a bigger pilot or is this really the “scale-up”, that’s the big question! In the development sector, especially in the international education arena, we are witnessing a huge number of pilots and with pilots, we are experimenting, and then from the experiment, if you actually identify a permanent solution, which is sustainable, that can be called a ‘scale up’ model. I’ll give you an example, you are doing a reading, writing, and critical thinking program for primary school children. I start in 10 schools or 100 schools in my community, then I want to move it to the state or national level, and eventually, the public system owns it and actually implements the program as part of their National or State implementation strategy. This program will hence become part of the national curriculum and will become part of the teacher training program of the government. Now, this is only the technical side, but what happens with the real thing, which is “money”? Who is paying for all of this?

Right now, in the LLF structure, this is what is so interesting and honourable for me to be associated with, which is that it is a homegrown program and it’s a homegrown financing program which we call domestic resource mobilisation or public financial management. If you are not familiar with the concept of domestic resource mobilisation and public financial management, think of it like this – we are getting all the donor money from outside for doing a lot of stuff right? Many times most of the end-users are waiting for money from donors and the donors will pay for projects and projects will continue from A to Z and then we finish the project and the donor may or may not want to continue. In that case, you don’t have the sustainability of your program. If there is no money from the donor, then the project stops. But ultimately, did the government own anything from the programs or projects that actually became part of the government system or the public service system which may be sustainable beyond the project cycle?

One part is the technical piece, as I mentioned, that the government took some part of curriculum reform, some part of teacher training, some part of materials that the project developed for children. But then who is paying for this after the project ends?

The government is actually taking this as a priority and saying that we will include this in our budget and continue the project with our own funds and the government resources. That is one kind of domestic resource mobilisation.

The scale-up process is also hugely impacted by the political issues. With elections, the political climate changes very frequently and balancing between what the Central government, State government and the local political parties wants, isa huge challenge. Another issue is sustainability. I have seen and heard a lot of success stories at LLF, that some of the activities are moving beyond the cycle. And what do I mean by the cycle, is the political cycle. Elections happening, changing government, new state Ministers getting appointed. But then your program did not stop. This is amazing progress in the scale-up process. I don’t think we talk enough about this in a scale-up discussion, which is that when you have your own cycle of success it is not impacted by the political and regime changes.

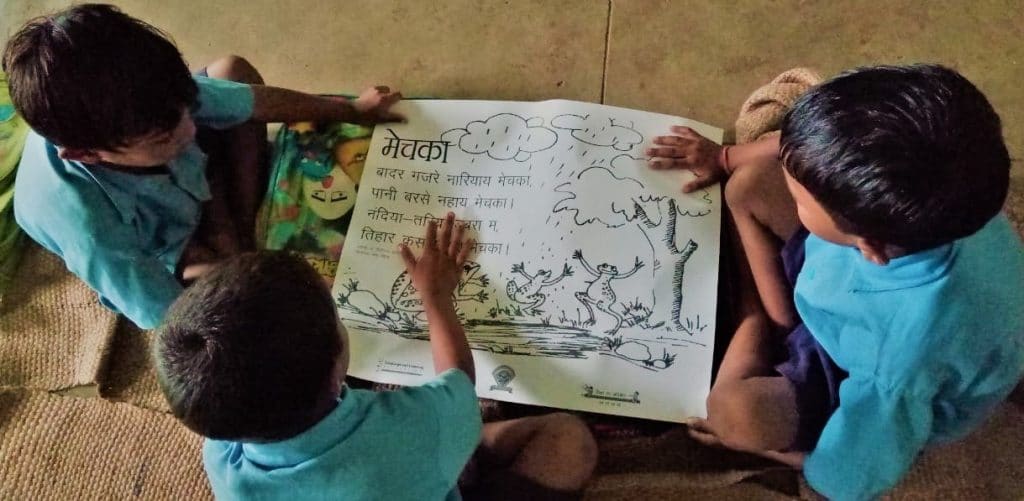

So we talked about the policy level issue, we talked about the financial issues, the third piece is Community’s engagement and acceptance. Are the children, the schools or the government in Orissa, Bihar or Haryana, wherever you are working, being impacted because you are there (LLF intervention) and you are facilitating all of this, or they are actually initiating these activities?

Maybe in the beginning we were the facilitators, policy advocates or the catalysts because we wanted to bring the issue to the limelight but then did we start taking a back seat and put the community in the driver’s seat? If the state government officials or the community leaders are actually taking lead in the activity or not is what matters. Is it on paper only or is it really happening? So this is also part of the scale-up discussion.

So scale up doesn’t mean an increase in numbers. I think there is a misconception about scale-up, which is that if we go to more schools, we scaled up. This is not what it means. Scaling up is very closely connected with sustainability. I managed to scale my program but then can I maintain the scale?

Maintenance is a very big issue because a lot of organisations can bring millions of dollars and they can rapidly grow but once the program ends and they leave does the program sustain or does everything go back to the old ways? Will you call that scaling up, was there ever a true impact?

So what will then impact mean and how can one measure true impact?

Now, the impact measurement is a very serious discussion. So if it is a real impact that you want to see in children’s development or success of the children in their communities, it might not be possible through the project life cycles, especially with the external funding life cycles. So if somebody says that we have measured the impact, it’s hard for me to believe, because it’s not possible to do impact measurement in three or five years. Let me give you a real example of impact, my parents put a lot of effort into educating me, and then I actually worked hard in my own life, now I am successful. Well, that’s the impact. Now you want to go back and measure this from my childhood, you actually can start doing empirical data collection and see how things progress because of the initial investment in my early life. The context, the support of the community, the schools, the pedagogy, everything had a certain impact on my success in life. So it actually takes a longer cycle timeline to measure true impact.

If you want to see the impact on the child you are working with today, you need to have empirical data for almost 20-25 years. That doesn’t match with our project life cycle thinking, because in 3 years or 7 years you have another project. So this is why I believe that impact measurement is only possible in the process.

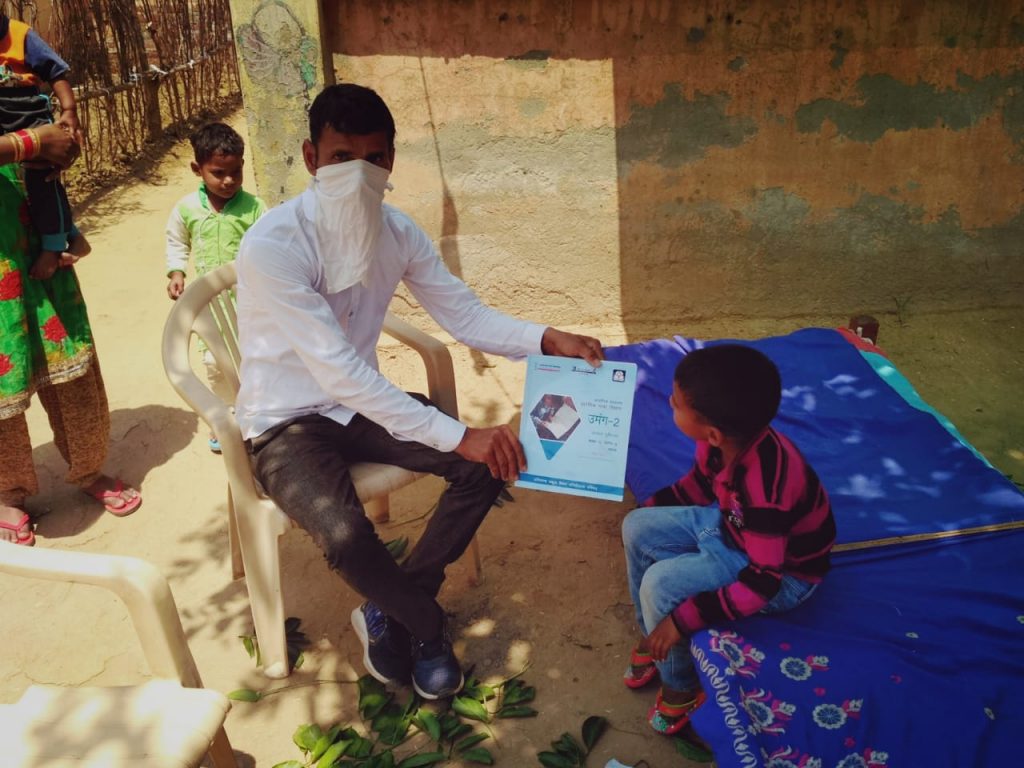

I always say that how people measure impact is really important. It’s a question of ethics because it is a question of what we measure. Mostly we measure impact based on the collection of process and performance data. That’s fine because what you want to talk about is that we were working in ten schools, a hundred schools, we worked with 10,000 children, now we work with 100,000 children. That actually impacts in a way that is data related, but the impact in the real sense will be measured by answering questions like-that did it really change anything or we sometimes say we efficacy, efficacy happens or not, that actually is a long term empirical data issue. How does this connect the measurement issue and the scaling up issue? This actually goes together because another kind of intellectual lingo that I want to use is something called Fidelity of implementation. This is also very important as we research our data because day to day we are implementing our programs and we want to see what is happening in our implementation. Now think about the scenario when you are starting a project and you are planning it for the future, we actually don’t know the future. So a lot of things you are planning and proposing now, when you propose you bring your best out, right? What you propose is not what always happens in the project life cycle, and that actually is the Fidelity of implementation, what I originally planned and what changed when I was implementing. So, what you proposed originally and the things coming at you while you are implementing the project, external issues, calamities, political reasons, covid everything will have an impact on your implementation. The difference between the original plan and what actually happens is the Fidelity of implementation. So this also impacts the project and the learning of children.

So according to the Pilot and Scale up definition you have given, once you experiment you figure out your strategies, you implement it to a larger number of schools, in a bigger space and that’s how you scale up. What I wanted to understand is that given it’s a social experiment in a way where there are factors which are not controllable, every time you take it to a bigger pace there are newer issues coming up, so there is some amount of experiment involved no matter what. So does that change the definitions or just the strategy becomes a pilot and the rest of the program remains a scale up?

This is a very intellectual and very deep question. This is good because you are thinking in the correct structure, there has to be certain fundamental attributes of what you are trying to do so it’s universally acceptable. What are you trying to universally accept as a parameter or framework is that you want children to learn. That is not changing. This is given and then the next question would come, What are you wanting for them to learn? They can read and write in their Mother Tongue now but then they are supposed to comprehend which is the next level. Then they will be learning critical thinking and problem-solving skills. If this much we are able to achieve it’s amazing because that is your fundamental need now. Your geography might change, your context might change, the numbers may go up or down. Those are all fine and you will bring different solutions to fix those issues. But your core mission does not change. The question is, if it is being taken up only by you or is it taken up by the entire community which accepted it and the government system or the public system accepted the idea. Now think about this from the health sector point of view. I always give the health sector example because they are much ahead of the education sector. Let’s look at just the COVID situation. We will continue to update and upgrade our Covid vaccine because the virus is changing its own patterns and structures but then the core mission remains the same. We want all of us to be safe and protect ourselves against the virus. Hence, vaccines are important, but those are not changing the fundamental core issue of fighting the disease.

The first example that you had given in the domestic resource mobilisation involves a strong component of sustainability. The second one, where we are talking about mobilising the resources available domestically through various forms, does not involve a sustainability component. So, when we look at domestic resource mobilisation, should sustainability be an important part from the inception or we can choose as and when required?

No, absolutely. Sustainability is always part of our discussion because sometimes we can also get into philosophical debates about what is sustainable? The point is, is it sustainable for the parameters or framework that you are trying to implement. Sustainable in the sense that I’m doing something for the child, so is the child getting what the child is supposed to get and are they thriving? I’ll give you a simple example. I did my project in the summer, it’s a school dropout prevention program. This was with the most vulnerable community there. My job was to bring the children back to school because 78% of children were not coming to school, they are dropping out because of a million reasons. The issue was what is sustainable, not only to bring them back to school but to maintain the sustenance of the children till the fifth grade. So the question is are they completing school? Are they learning what they are supposed to learn? Did they make it to secondary school? So the question would remain about sustainability. You asked about resource mobilisation and sometimes people might say, this is free, nothing is free, there is an economic value on every single thing. So the point is, is it from the outside external resources or is it coming from within the community where the community is supporting this work and slowly it moves into the community’s hand that the district education officer is now so motivated that he thinks that all my teachers need to be really high skilled teachers, and this becomes part of my normal life. I’m not doing this because LLF trained me.

So those are different parameters of sustainability and scale of resource mobilisation. And finally, the budget piece, which is crucial. Now, most of the people in the public education sector don’t talk about the budget side but this is something we all need to become more educated about which is how the education sector is budgeting and how the education sector’s financial support works. When I talk about the government taking something as part of their budget, that has two parts: the bureaucracy and the budget if the activities are in their budget, you know they have taken it into the heart because teacher development or supply of materials to the children or the extracurricular activities you are doing in the school, it should become part of the government’s budget cycle. So this is also resource mobilisation and domestic resource mobilisation is connected with the public financial management which is the budgeting of the government. And does that budget look like anything LLF is doing there? Is it part of their budget cycle? Are you advocating for those changes in their budget cycle? So not only including our activities but this is a very important part of our job as well, to do the policy lobbying and influencing that they actually understand the importance and put this in their budget.

Conclusion:

We need to really decolonize the development paradigm. If we need 4 reform programs in any given country to fix the education sector with millions of dollars spent but still 70% of children can’t read and write in their mother tongue, something surely isn’t right! What we need to think about is real demand driven programs that are owned by the community, our role will surely change in this structure. We remain the facilitators, catalysts and/or partners in true sense. But this role is to help build local capacity and system strengthening for their own sustainable future. And yes, if the mission is accomplished, we need to move on! It may seem a zero sum game, but it’s not, because within the changing world new demands are created and we will remain involved in international and local development in different ways!

Recent Comments